Whereas: Stories from the People’s House

Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives

Whether debates are brief or last deep into the night, official reporters are on hand. When a heated argument about a tariff continued for two wordy weeks in 1890, reporters stuck it out to record history. “It is impossible to conceive the difficulty of reporting the House during such a discussion,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported. “The stenographers of the House of Representatives have been worked nearly to death.”

Transcribing Congress

During early Congresses (and continuing through today), the House recorded minutes in the House Journal. The Journal provided summaries of each day’s proceedings, and Congress decided in its first decades that detailed, word-for-word transcriptions would be too expensive. But by 1848, advances in shorthand made verbatim transcriptions physically and financially possible. As Members spoke on the House Floor, an official reporter furiously jotted notes in the symbols of shorthand. One print from 1900 shows the difficult work of the official reporter: A diligent stenographer stands in the aisle of the House Chamber, jotting notes on a limp page as a Member gives an impassioned speech, arm flung out. Other Representatives chat throughout the chamber, undoubtedly creating even more noise.

Technology

Microphones improved the acoustics of the chamber after they were permanently installed in 1938, enabling stenographers to sit still and take advantage of a technological innovation—the stenograph. Invented in the late 19th century, the stenograph allowed reporters to type rapidly, rather than take notes by pen.

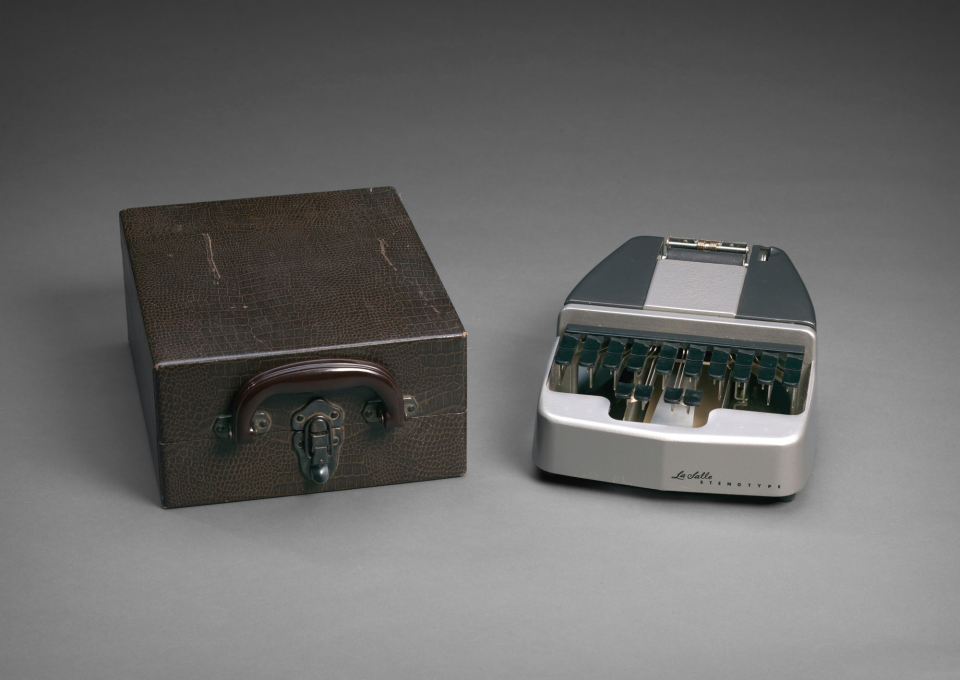

Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives. Stenographers used this machine to record verbatim transcripts of congressional proceedings and meetings.

Official reporters began using this La Salle Stenotype in the House around 1950. The machine’s keys consist of consonants and vowels, which stenographers struck simultaneously like a musical chord on the piano, producing shorthand notations. As with a typewriter, the keys hit a ribbon with ink, printing shorthand symbols on paper. The machine automatically advanced the paper. At the end of the 20th century, both the stenographers on the House floor and the committee reporters transitioned to digitized machines, which automatically translated the shorthand into standard English.

Relay on the Floor

From the earliest days of precise transcription on the House Floor, one stenographer took notes for a shift, and then hurried to the transcribing room to edit and deliver the notes to a transcriber. As the first stenographer dashed to the transcribing room, a second took over reporting on the House Floor without missing a beat. Meanwhile, the transcriber typed out the notes, translating them from shorthand into standard English, and rushed the pages to the Government Printing Office. There, printers prepared the text for Congressional Record, which appeared early the next morning. The Washington Post recounted the story of “a member who was still talking after 11 o’clock, finished and caught the 12 o’clock train for New York. The next morning he had a copy of the Congressional Record at his breakfast table in New York,” thanks to the speedy work of official reporters and printers.

Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives. In the thick of the action, a stenographer reported a hearing of the Special Committee to Investigate Campaign Expenditures in 1944.

On top of the long hours and breakneck pace of transcription, stenographers faced numerous other challenges. Some Representatives mumbled, and others spoke at a frightening clip. In 1891, the Post noted that stenographers feared New York Representative William Bourke Cockran, who averaged 180 words per minute: “It is said that when he went to Congress the official reporters thought they had been struck by lightning.”

In Committee Hearings

Understanding and accurately reporting the complicated, varied topics of committee hearings proved another challenge. “One day you’re listening to Armed Services and things about the military, and all the acronyms, and all the weapons systems and things,” Strickland said. “Then the very next day, you’re in Natural Resources and they’re talking about some salamander in a pond somewhere. Now you’re trying to figure out what they’re talking about.” When official reporters went on strike in 1912, committees realized the importance of stenography, and a special committee’s investigation ground to a halt.

Making Music

Stenography, as Strickland points out, is similar to playing music. Like a pianist, the stenographer strikes the keys by feel, quickly and confidently. However, musicians have the advantage of knowing which note comes next. In the House of Representatives, on the other hand, official reporters “never know what’s coming. We just have to sit there and wait for the words to come out of their mouths, and still do it with the facility of a pianist playing Chopin.”

Article courtesy of: Office of Art & Archives

https://history.house.gov/Blog/2019/July/7-23-stenotype/?fbclid=IwAR0SdRIqlgU4KV0RBcl-MX0Q9B3-tcWkuQ30OssfaQGfGdxQR-HzR__Pizs

Sources: Atlanta Constitution, 7 January 1894; New York Times, 9 January 1912; St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 18 May 1890; Washington Post, 15 November 1891, 3 March 1929; Stenograph L.L.C., History of Writing Machines; and Made-in-Chicago Museum, Stenograph History.